In the Tale of The Fall of Gondolin are two of the most significant powers in the world. There is Morgoth of the uttermost evil, unseen in this story but ruling over a vast military force from his fortress of Angband. Deeply opposed to Morgoth is Ulmo, second in might only to Manwë, chief of the Valar: he is called the Lord of Waters, of all seas, lakes, and rivers under the sky. But he works in secret in Middle-earth to support the Noldor, the kindred of the Elves among whom were numbered Húrin and Túrin Turambar.

Central to this enmity of the gods is the city of Gondolin, beautiful but undiscoverable. It was built and peopled by Noldorin Elves who, when they dwelt in Valinor, the land of the gods, rebelled against their rule and fled to Middle-earth. Turgon King of Gondolin is hated and feared above all his enemies by Morgoth, who seeks in vain to discover the marvelously hidden city, while the gods in Valinor in a heated debate mainly refuse to intervene in support of Ulmo’s desires and designs.

Into this world comes Tuor, cousin of Túrin, the instrument of Ulmo’s designs. Guided unseen by him Tuor sets out from the land of his birth on the fearful journey to Gondolin, and in one of the most arresting moments in the history of Middle-earth, the sea-god himself appears to him, rising out of the ocean in the midst of a storm. In Gondolin he becomes excellent; he is wedded to Idril, Turgon’s daughter and their son is Eärendel, whose birth and profound importance in days to come is foreseen by Ulmo.

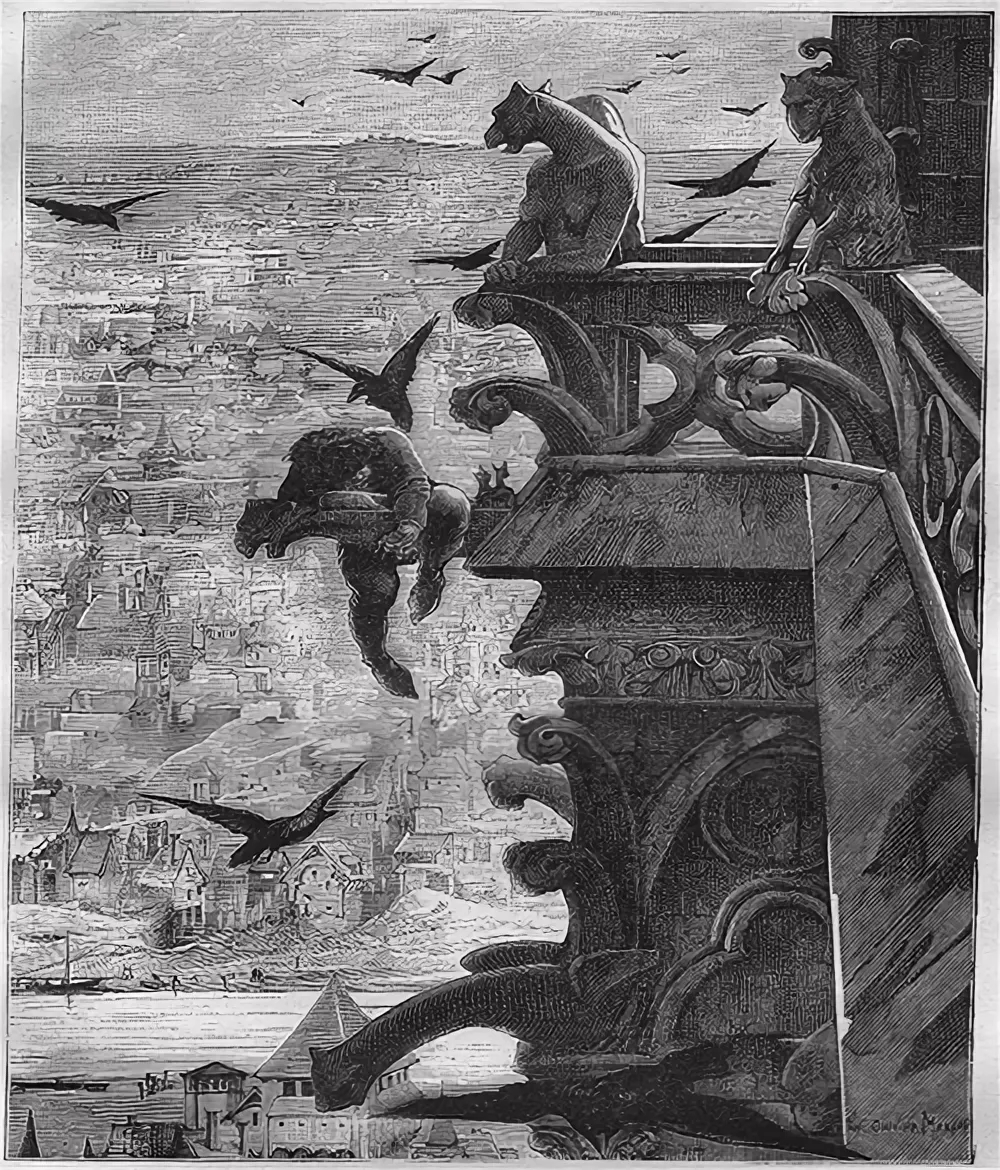

At last, comes the terrible ending. Morgoth learns through an act of supreme treachery all that he needs to mount a devastating attack on the city, with Balrogs and dragons and numberless Orcs. After a minutely observed account of the fall of Gondolin, the tale ends with the escape of Túrin and Idril, with the child Eärendel, looking back from a cleft in the mountains as they flee southward, at the blazing wreckage of their city. They were journeying into a new story, the Tale of Eärendel, which Tolkien never wrote, but which is sketched out in this book from other sources.

Following his presentation of Beren and Lúthien Christopher Tolkien has used the same ‘history in sequence’ mode in the writing of this edition of The Fall of Gondolin. In the words of J.R.R. Tolkien, it was ‘the first real story of this imaginary world’ and, together with Beren and Lúthien and The Children of Húrin, he regarded it as one of the three ‘Great Tales’ of the Elder Days.

Christopher Tolkien, J. R. R. Tolkien's son, has done great detailed work in evaluating and ordering his father's notes regarding Middle-Earth and the mythology he had created central to it. This was not easy work. He has spent years of effort reading all of his father's numerous notes written over multiple years. Christopher has ordered and deconflicted these many tales. I cannot imagine the magnitude of this work.

To be thorough in his publishing of his father's thoughts, Christopher recorded in this book the different version of the tale, and he notes his selection of essential aspects of the story that he chose in his telling of the tale. Christopher's writing of The Fall of Gondolin is engaging and beautiful in keeping with his father's writing style.

I am not taken by the details of Middle-earth mythology. I skipped over large sections of this book that provided retellings of the story from his father's copious notes. Christopher had already noted these in his telling. The myth of Gondolin's fall as told by Christopher was enjoyable and complete. I believe the son performed due diligence in providing all the notes.